[Review] Shaolin Soccer 少林足球 (2001)

Colonial consciousness and "Sino washing" Hong Kong culture

Hong Kong comedies rarely reach a global audience. Cantonese’s pun-heavy nature coupled with Hong Kong society’s tendency towards low-brow humour makes the language difficult to translate. Even when successfully translated, the way Cantonese humour manifests itself on the screen often leaves foreign viewers scratching their head, questioning what exactly is so funny about the near-constant vulgarity or the endless series of nonsensical plot points.

There are many theories as to why this type of slapstick humour - known as mo lei tau 冇厘頭 - has come to define Hong Kong comedy. Some attribute mo lei tau to a broader “Chinese” way of thinking. Confucianism has always considered humour to be a sign of intellectual shallowness; an expression of extreme emotion and social informality. It was only in the early 1900s that Chinese people started to see “humour” (幽默 ) as a humanistic virtue that traditional Chinese society sorely lacked. And because this positive view of humour is still so recent, “comedy” remains a culturally marginalized genre that is often regarded by wider society as non-serious, shallow, and escapist.

However, the “non-serious” nature of mo lei tau does not mean that the genre does not provide any “serious” insights into Hong Kong culture or identity. In fact, as Stephen Chow’s groundbreaking Shaolin Soccer (2001) shows us, mo lei tau films represent a distinct type of Hong Kong identity, one that emphasizes and internalizes cultural tropes that reinforce an attitude of “belonging” to the motherland: mainland China. The widespread popularity of these tropes highlight a strong desire from many Hong Kongers who wish to remove every trace of colonial British heritage, no matter how contradictory (or impossible) it might seem. The way Hong Kong Football is treated in Shaolin Soccer is one example.

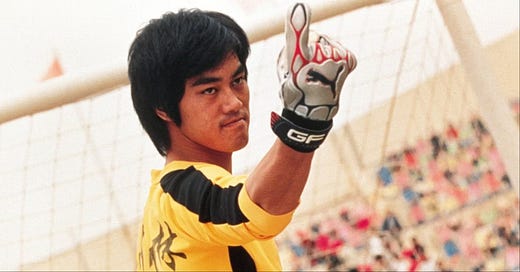

Shaolin Soccer follows an impoverished Sing (Stephen Chow), a former Shaolin monk with the moniker “Mighty Steel Leg,” who seeks to bring Shaolin kung-fu to the masses through association football. The movie begins with a greyscale flashback to the 1980s. Fung (Ng Man-tat) is a Hong Kong soccer star who is offered a cheque from his teammate Hung (Patrick Tse) to throw the game. Fung violently berates Hung but ultimately accepts the money. During the match, Fung deliberately misses a last-minute penalty kick and his team loses. Angry spectators rush onto the pitch, and one of them breaks Fung’s shooting leg with a baseball bat, ending his career.

Twenty years later, Hung is a successful businessman who owns a football team while Fung walks with a limp and works odd jobs for Hung’s organization. After a training session at Hung’s team building, Fung approaches him and asks to coach the football team. In response, Hung mocks Fung by revealing that it was he who hired the angry mob to break Fung’s leg.

Despondent, Fung drunkenly roams the streets where he comes across Sing, a dumpster-diving vagrant who makes a living selling discarded recyclables and spends his days trying to convince passers-by to take kung-fu lessons from him. After hearing Sing’s solicitation, Fung rejects him, deriding Sing’s poor circumstances and sneering at his dreams of spreading Shaolin kung-fu across the world. We glimpse Sing’s flirtations with poverty as he tries to steal mantou from Mui, a woman with severe acne who uses Tai Chi to make food. They soon become close friends but Mui disappears after her confession of having feelings for Sing are rejected.

Sing seeks out his older (Shaolin) brother “Iron Head” (Wong Yat-fei) at the bar he works at and pitches the idea of creating music to spread Shaolin kung-fu. Initially hesitant, Iron Head is bullied into setting up a live concert by his abusive boss who threatens to dock his pay if he doesn’t find a way to entertain the bar’s triad-involved regulars.

The concert is a spectacular failure and the bemused triad violently assault Sing and his brother. Sing challenges the triads to a fight and defeats them all with just a soccer ball, despite being outnumbered. Coincidentally, Fung witnesses the fight and is awestruck by Sing’s powerful legs. He offers to coach Sing, who is compelled by the idea of promoting kung-fu through soccer. They convince Sing’s five Shaolin brothers (Iron Head, Hooking Leg, Iron Shirt, Empty Hand, and Lightweight Vest) to join their team.

Fung organises a friendly match with a team of triad thugs. During the match they violently attack Team Shaolin, who are initially helpless, but the physical beating ultimately awakens their dormant Shaolin powers. They easily dispatch an awestruck Team Thugs, who ask to join Team Shaolin. Now with a complete squad, Team Shaolin enter the open cup where they progress with ease. Hung hears about their success and scrambles to find ways to ensure that his team - Team Evil (literally) - will win the cup again. He contacts Fung and offers him money, who calmly rebuffs him. Angered, Fung bribes the cup officials as well as purchasing an American doping programme for his team which gives the players superhuman strength and power similar to those of Team Shaolin.

The two teams meet at the final, and Team Shaolin are viciously outmatched. Officials turn the other way as Team Evil injures one Shaolin player after the other, with the goal of forcing Team Shaolin into a forfeit. With six players left with no goalkeeper, Shaolin are asked to forfeit when Mui suddenly appears and offers to go in goal. She and Sing combine their powers to create a tornado blast which sends the ball hurtling into the opposition goal while blasting away all of Team Evil’s players, winning the match.

Some time later, Hung is imprisoned for doping and Team Evil players are sentenced to lifetime bans. We see Sing jogging on the street where he first met Fung, observing as the people around him use Shaolin kung-fu in their everyday lives. As he jogs into the distance, his lifelong dream now a reality, a giant billboard ad reveals that Sing and Mui are now global stars who have won championships not just in soccer but many different sports.

Shaolin Soccer was a global hit that put Stephen Chow on the cinematic map. At the time, it was the highest-grossing Hong Kong film ever, only surpassed a few years later by Stephen Chow’s next comedic hit Kung Fu Hustle. But lurking underneath the lighthearted themes that make the film globally appealing - soccer, kung fu, rags-to-riches - are undertones of a suppressed colonial-era discontent that has finally bubbled to the surface in post-Handover Hong Kong. For the average viewer, Shaolin Soccer is nothing more than a “Chinese” or “Hong Kong” movie - but it is precisely this association that misrepresents Hong Kong history and muddies our understanding of Hong Kong society.

Before the 1970s, Hong Kong was considered the “Football Kingdom of the Far East.” Like elsewhere with substantial British influence, football became a part of Hong Kong’s social and cultural fabric since its early days as a British colony, claiming a firm piece of the city’s identity as it witnessed rapid changes over the course of the century. Initially, ethnic Chinese struggled to participate in Hong Kong footballing events due to racial segregation - sporting clubs like the Hong Kong Cricket Club (1851), the Hong Kong Jockey Club (1884), and the Hong Kong Football Club (1886) were exclusive to Europeans. Yet, as Ip Kwai Chung tells us in Soccer in China (one of the few existing social histories of Hong Kong football culture) such exclusion did not stop Chinese boys from watching, imitating, and spreading football beyond the barbed fences.

Over time, as segregation declined and Chinese exposure to the sport increased, locals began forming their own teams. In 1914, South China - 南華 - was the first all-Chinese team to play against an all-European Hong Kong Football Club, shocking spectators with a hefty 5-0 victory. This win launched South China onto the Hong Kong football scene, spurring the formation of more local clubs as well as the establishment of competitive local leagues. South China also became a symbol of Chinese football, representing the Republic of China in many diplomatic friendlies all over the world until the communists took power in 1949. Lee Wai Tong became one of the world’s most famous names, as a player, coach, and later a vice president of Fifa.

Over time, Hong Kong football started to attract foreign talent. Walter Gerrard (daai6 seoi2 ngau4 “Water Buffalo”), Derek Currie (“Jesus”), and Jackie Trainer were several early journeymen to make professional footballing careers in Hong Kong. Their success paved the way for other foreigners to consider Hong Kong as a place to build a respectable footballing career. Even as Hong Kong football slowly declined after the 1980s, the city still had a robust professional scene where foreign players could live off football alone without the need for part-time work. Today, the Hong Kong Premier League is full of foreign players from England to Japan to Costa Rica to Brazil. Paulo César, Hélio, Fernando, Everton Camargo, and Juninho are all Brazilian-born, Hong Konger-naturalised footballers who represent the Hong Kong national men’s team. Michael Udebuluzor, born and raised in Hong Kong and son of Nigerian footballer Cornelius Udebuluzor, also plays for the Hong Kong team, plying his trade in the German third division.

The Hong Kong national football team at Mong Kok Stadium. Photo: Hong Kong Football Association. 2015.

Football in Hong Kong has always been an international sport. Indeed, it should not come as a surprise given Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan branding and global outlook. Yet, as the themes in Shaolin Soccer demonstrate, the political undercurrents of a domineering “Britain” versus an anti-colonial “Chinese” have obfuscated us from remembering Hong Kong sport’s diversity history. Hong Kong’s multicultural and multiethnic fabric rarely reaches world media - over and over, Hong Kong’s heterogeneity comes as a source of surprise, and sometimes even met with active derision. Ethnic diversity in Hong Kong is an unspoken rule; it is reluctantly recognised, but never championed.

Successive regimes have always strived to erase reminders of their predecessors, and Hong Kong is no different. The debate over whether to remove symbols of oppression - colonial statues, buildings, street names - occurs periodically in countries all over the world, Africa to Europe. In Hong Kong, colonial erasure has been a contentious topic since the 1997 Handover, and often met with fierce resistance. There are many in Hong Kong who feel attached to the city’s colonial past, symbols of oppression be damned.

Curiously, this attachment to historical authenticity hasn’t gained much traction in cultural production debates. While criticism against cultural propaganda and mainland Chinese nationalism are common, these reactions usually fall within a colonial/anti-colonial perspective. “Erasing Hong Kong’s past” means removing colonial architecture, flags, institutions, and streets; rarely do people refer to the cultural silence of Hong Kong Russians, Vietnamese, or Indians. Similarly, mainland Chinese nationalism manifests as either “Hong Kong is China” or “Hong Kong is not British.” Everything else is irrelevant or at best, unimportant.

This binary permeates throughout Shaolin Soccer. “Team Evil” is owned by a corrupt businessman who wears Western suits and buys American drugs to cheat. Opposing them are a band of natural martial arts practitioners who rely on belief and determination to overcome insurmountable odds. This allegory is an old but powerful one: Western power and money versus Chinese morality and authenticity. It is possible to exist in modern life without selling out to Western values. In one scene, Iron Shirt rebuffs Sing’s attempt to recruit him by flipping a coin - life is either heads or tails; there is no middle ground. Yet, as he bends over to pick up the dropped coin, he is surprised to find it perfectly balanced between pavement cracks. Nothing is impossible.

We see this story play out in almost every single character arc. Hung’s greed is his ultimate downfall, while Fung achieves redemption by casting away temptation and living honestly. Sing and his brothers, by sticking to their authentic Chinese selves despite the hardships, are rewarded. For Sing especially, his dream of seeing a world embrace Chinese values proves not to be foolish but wise. Mui sheds her self-loathing and grows into a beautiful, successful kung fu practitioner.

While this narrative does highlight an important perspective in Hong Kong society, it does not paint a full picture, and instead - perhaps unwittingly - furthers the problematic assumption of Hong Kong Chinese homogeneity. Representation in media matters not because of increased sales or political correctness, but because it challenges stereotypes and fosters community. This is not to say that movies like Shaolin Soccer aren’t representative or shouldn’t be made. Only that we should be aware of what might be missing in artistic productions, and be cautious not to silence voices or push totalizing narratives.

Ironically, despite being shot mostly in China, the film was initially banned on the mainland as a result of Chow's refusal to placate government censors. But it is important to separate Chinese politics from Chinese identity; too often, people misattribute those from Hong Kong who display a strong sense of Chineseness with an allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party. Shaolin Soccer reminds us that we must approach complicated topics like culture and class through a historically-informed lens that slices through the murky clouds of contemporary politics. We must remain vigilant against simple binaries like “Chinese” versus “British” or “freedom” as opposed to “colonialism.”

(Walter Gerrard, Derek Currie and Jackie Trainer arrive in Hong Kong on September 10, 1970. Ian Petrie is next to former Caroline Hill owner Veronica Chan, with future Hong Kong coach Kwok Ka-ming on the right. Photo: SCMP)